In this

issue

WELCOME

NURSING SCIENCE

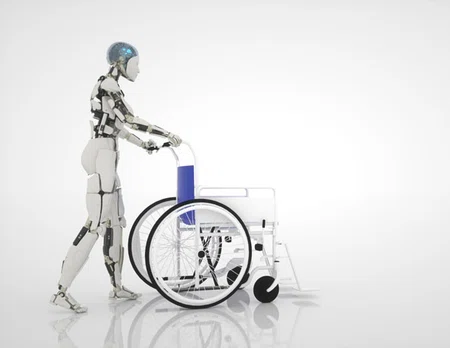

Attitudes toward the use of humanoid robots in healthcare

Preparing for the Future by Understanding the Past

EDUCATION

PRACTICE

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

FROM OUR TEAMS

Looking to the Future with our Patient Care Assistants

The Future of Nursing is Bright…But What if Being a Nurse is Not for You?

ABOUT DISCOVERN

NURSING SCIENCE

Preparing for the Future by Understanding the Past

By Michelle C. Hehman, PhD, RN

By Michelle C. Hehman, PhD, RN

4 MIN READ

In an increasingly complex and technology-driven world, nurses are well-positioned to address both the longstanding and future health challenges of diverse patient populations. Nurses work in and across communities, collaborate with other health disciplines and bring a unique set of knowledge and values to support the well-being of patients and families. The future of nursing will require innovative approaches to professional education, scholarship and practice to continually improve outcomes and advance global health equity. Many institutions are embracing digital technology to facilitate growth in each of these nursing spheres, and we must be ready to initiate, partner in and lead the integration process.

While it seems counterintuitive, a historical perspective on the relationship between nurses and technology can offer insight into challenges we may face in the future. In the nearly 150 years since the first nurse training schools opened in the United States, professional nursing practice has evolved largely because of advances in medical technology, scientific knowledge and diagnostic instruments. Throughout that time, nurses have used a variety of tools — from mundane domestic items to complex monitoring systems — to assess, treat and heal patients. Understanding how nurses have responded to new technology in the past, both the successes and the failures, can illuminate enduring issues and guide our interactions moving forward.

Historical analyses demonstrate how nurses frequently adopted technology as a means to highlight our unique expertise, but our ability to effortlessly manage, troubleshoot and improvise with the devices ended up reinforcing our professional invisibility (Sandelowski, 2000; Fairman & D’Antonio, 1999). Prior to World War II and the introduction of high-technology wards in the hospital, nursing practice involved environmental control, emotional support and everyday domestic tasks like feeding and bathing. Completion of these duties required constant physical interaction, the unaided use of all senses and strong but dexterous hands. What differentiated trained nursing from everyday domestic work, however, was the application of these manual skills in conjunction with specialized knowledge. Nurses became particularly adept at improvising everyday items for therapeutic purposes, turning baths and beds into specialized treatments by altering their design or application. Unfortunately, the complex decision-making involved in these transformations remained invisible, perpetuating a low social status for the profession.

As technology in the hospital became more complex and pervasive in the 1950s and beyond, nurse management of advanced monitoring systems and diagnostic tools blurred the boundaries between nursing and medicine. Unfortunately, physicians maintained practical authority over new technology despite shared use with nursing staff. Physicians completed the high-status, highly visible work of prescribing and analyzing data from these devices, while the nurses’ work remained invisible. Overseeing both the patient and the devices required an intelligent interplay between expert nursing knowledge and technical proficiency, but “this knowledge was either not recognized or completely minimized, even by nurses themselves” (Sandelowski, pp.64).

Today’s healthcare environment demands that nurses navigate a technology-heavy space, figuring out how to perform higher-touch activities like physical assessments and bathing around the increasing paraphernalia of therapeutic devices. Despite being the primary end-users, very few technology developers have incorporated nurses into the design and implementation process, often leading to inefficiencies and process gaps. This increases the workflow burden on nurses, potentially leading to job dissatisfaction, increased error risks, and/or patient safety issues (Zuzelo et al., 2008).

So what does all of this mean for the future of nursing? First and foremost, nurses need to become much more involved in the process of designing, acquiring and integrating new healthcare technology. Our unique position affords insight into the small- and large-scale complexities of the care delivery space, and organizations need to recognize the value of a nursing voice in technology decision-making. We also need to highlight the specialized work involved in managing therapeutic devices and design curricula that offer opportunities for nurses to develop expertise in emerging fields like robotics, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality. New technology holds the promise of providing better and more effective care for our patients, but we need to ensure our place in its creation and deployment.

References:

Sandelowski, M. (2000). Devices & desires: Gender, technology, and American nursing. The University of North Carolina Press.

Zuzelo, P.R., Gettis, C., Hansell, A.W. and Thomas, L. (2008). Describing the influence of technologies on registered nurses’ work. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 22(3), pp. 132-140.

Related Articles

NURSING SCIENCE

Attitudes toward the use of humanoid robots in healthcare

EDUCATION

Virtual Reality and Artificial Intelligence in Nursing Education

Contact us at CNREPHelp@houstonmethodist.org

Questions or comments?

© 2022. Houston Methodist, Houston, TX. All rights reserved.